History of the city of Miletus

Miletus’ history far exceeds the information we gain from written documents. Archaeologists have found traces of human settlement dating back to the Chalcolithic. The earliest buildings were identified on the flat hill near the Temple of Athena. They came from eight Bronze Age phases ranging from the late Chalcolithic until the end of the Mycenaean era. Ancient sources tell us that Miletus was either founded by a certain Miletos of Crete or by Sarpedon from the Cretan town of Miletos on the site of a Carian settlement. To the Mycenaeans, Miletus was the only important settlement in Asia Minor. The Hittites conquered the settlement twice, once at the end of the fourteenth century BCE and once in 1200 BCE. They already called the town Milawanda when it was under Mycenaean rule. Soon after the second Hittite conquest, Miletus was destroyed.

According to historical sources, it was refounded by Ionian colonists in the eleventh century BCE. After that era, the next identifiable archaeological evidence dates back to the Archaic period (eighth–sixth century BCE), as this is when Miletus grew into one of the most important cities of the Aegean region. The city’s economic power was so great that many colonies were founded from it, with some sources speaking of more than 80. It also wielded military and political supremacy and was considered the capital of Ionia (Ioniae caput). The Milesian tyrants Histiaeus and Aristagoras started the Ionian revolt against the long reign of Persia in 499 BCE, which culminated in the defeat of Miletus in 494 BCE. The ancient historian Herodotus wrote that the city had been destroyed completely, its inhabitants massacred and enslaved. After the event, Milet was “empty of Milesians.”

Researchers dispute the extent of its destruction to this day, but the date is generally accepted as a crucial event in the city’s history. It also marks the decline of Miletus’ supremacy. In the fifth century BCE, the city had to pay a very large sum as a member of the Delian League and was eventually occupied by the Athenians after a failed attempt to leave the confederacy in the early second half of the fifth century BCE. It was not until the Ionian War that Miletus finally left the Delian League and became a Spartan base.

Map of Miletus (Miletus excavation 2022)

In 334 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered Miletus, but the city remained largely independent from the Diadochi after the collapse of the Macedonian Empire. This independence ended in 133 BCE, when the Kingdom of Pergamon was given to Rome, making Miletus a part of the province of Asia.

Although Miletus did not enjoy any special advantages as a Roman city, it had a well-functioning economy, and many stately new buildings were established in the city during that time. It was home to a Jewish and an early Christian community. In the middle of the third century CE, the Goths attacked Miletus, and the city walls had to be rebuilt.

Christianity replaced the ancient cults as the predominant religion between the fourth and seventh century CE. Miletus became an archdiocese in the sixth century. In the seventh, invasions from Persian and, later, Arab armies led to the construction of a new city wall that made the city smaller. Little is known about settlement during the more peaceful era between the ninth and eleventh century CE. It was only the new threat from the Turks that made fortification necessary again.

Based on the highly defensible fortified theater and the surviving palatial ruins, the name of Miletus became Palatia and later developed into Balat, the name of a nearby village to this day. The Turks conquered Palatia in the thirteenth century. During the time of the beylik of Menteşe, Miletus was a small but significant inland port with many far-reaching trade contacts and the residence of a Venetian consul.

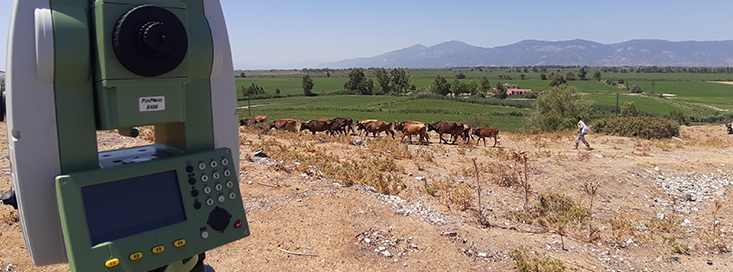

Archaeology and agriculture in Miletus. Source: L. Steinmann 2021

Archaeology and agriculture in Miletus. Source: L. Steinmann 2021

In the fifteenth century, Balat and its surroundings were finally subsumed into the Ottoman Empire. The settlement, which probably still had around 3500 inhabitants in the sixteenth century, lost its national significance. For a long time, the village of Balat (today called eski Balat, “old Balat”) remained within the long-forgotten city walls of ancient Miletus. After a severe earthquake in 1955, the village was relocated to its current site, around 1.5 kilometers further south. Balat is a lively village with a handful of small businesses today. Many of its over 1000 inhabitants work in the area’s countless olive groves, fields and gardens or lead their herds of sheep or cattle through the Milesian chora. Some have worked on the various excavation projects for many years, and the dig itself has become an integral component of the history of modern Balat.

Text: Mark Ohlrogge